freeCodeCamp

By Zubin Pratap

You may have heard the terms "Architecture" or "System Design." These come up a lot during developer job interviews – especially at big tech companies.

I wrote this in-depth guide when preparing for my FAANG software engineering interviews. It covers the essential software system design concepts you need to reason your way through distributed systems, and it helped me get into Google as an engineer, after more than 15 years of being a corporate lawyer.

This is not an exhaustive treatment, since System Design is a vast topic. But if you're a junior or mid-level developer, this should give you a strong foundation.

From there, you can dig deeper with other resources. I've listed some of my favourite resources at the very bottom of this article.

I've broken this guide into bite-sized chunks by topic and so I recommend you bookmark it. I've found spaced learning and repetition to be incredibly valuable tools to learn and retain information. And I've designed this guide to be chunked down into pieces that are easy to do spaced repetition with.

Let's get started!

"Protocols" is a fancy word that has a meaning in English totally independent of computer science. It means a system of rules and regulations that govern something. A kind of "official procedure" or "official way something must be done".

For people to connect to machines and code that communicate with each other, they need a network over which such communication can take place. But the communication also needs some rules, structure, and agreed-upon procedures.

Thus, network protocols are protocols that govern how machines and software communicate over a given network. An example of a network is our beloved world wide web.

You may have heard of the most common network protocols of the internet era - things like HTTP, TCP/IP etc. Let's break them down into basics.

Think of this as the fundamental layer of protocols. It is the basic protocol that instructs us on how almost all communication across internet networks must be implemented.

Messages over IP are often communicated in "packets", which are small bundles of information (2^16 bytes). Each packet has an essential structure made up of two components: the Header and the Data.

The header contains "meta" data about the packet and its data. This metadata includes information such as the IP address of the source (where the packet comes from) and the destination IP address (destination of the packet). Clearly, this is fundamental to being able to send information from one point to another - you need the "from" and "to" addresses.

And an IP Address is a numeric label assigned to each device connected to a computer network that uses the Internet Protocol for communication. There are public and private IP addresses, and there are currently two versions. The new version is called IPv6 and is increasingly being adopted because IPv4 is running out of numerical addresses.

The other protocols we will consider in this post are built on top of IP, just like your favorite software language has libraries and frameworks built on top of it.

TCP is a utility built on top of IP. As you may know from reading my posts, I firmly believe you need to understand why something was invented in order to truly understand what it does.

TCP was created to solve a problem with IP. Data over IP is typically sent in multiple packets because each packet is fairly small (2^16 bytes). Multiple packets can result in (A) lost or dropped packets and (B) disordered packets, thus corrupting the transmitted data. TCP solves both of these by guaranteeing transmission of packets in an ordered way.

Being built on top of IP, the packet has a header called the TCP header in addition to the IP header. This TCP header contains information about the ordering of packets, and the number of packets and so on. This ensures that the data is reliably received at the other end. It is generally referred to as TCP/IP because it is built on top of IP.

TCP needs to establish a connection between source and destination before it transmits the packets, and it does this via a "handshake". This connection itself is established using packets where the source informs the destination that it wants to open a connection, and the destination says OK, and then a connection is opened.

This, in effect, is what happens when a server "listens" at a port - just before it starts to listen there is a handshake, and then the connection is opened (listening starts). Similarly, one sends the other a message that it is about to close the connection, and that ends the connection.

HTTP is a protocol that is an abstraction built on top of TCP/IP. It introduces a very important pattern called the request-response pattern, specifically for client-server interactions.

A client is simply a machine or system that requests information, and a server is the machine or system that responds with information. A browser is a client, and a web-server is a server. When a server requests data from another server then the first server is also a client, and the second server is the server (I know, tautologies).

So this request-response cycle has its own rules under HTTP and this standardizes how information is transmitted across the internet.

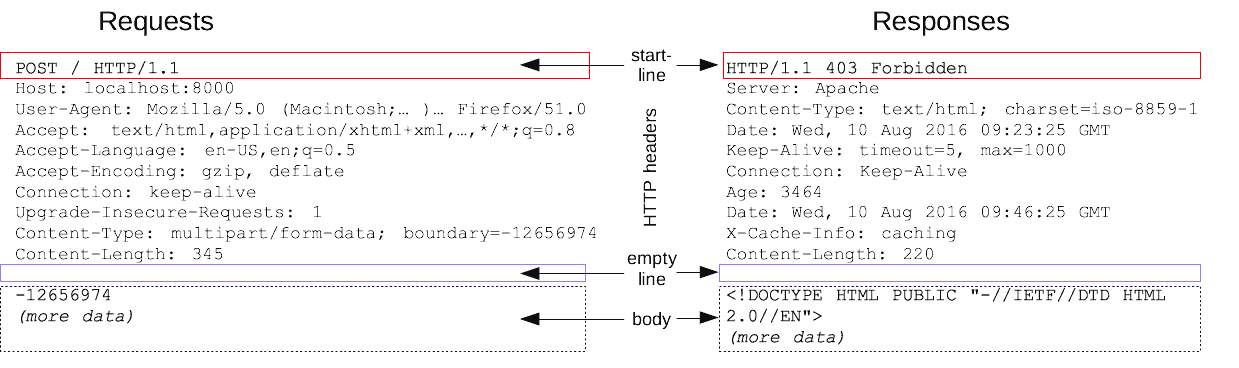

At this level of abstraction we typically don't need to worry too much about IP and TCP. However, in HTTP, requests and responses have headers and bodies too, and these contain data that can be set by the developer.

HTTP requests and responses can be thought of as messages with key-value pairs, very similar to objects in JavaScript and dictionaries in Python, but not the same.

Below is an illustration of the content, and key-value pairs in HTTP request and response messages.

source: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Messages

HTTP also comes with some "verbs" or "methods" which are commands that give you an idea of what sort of operation is intended to be performed. For example, the common HTTP methods are "GET", "POST", "PUT", "DELETE" and "PATCH", but there are more. In the above picture, look for the HTTP verb in the start line.

Storage is about holding information. Any app, system, or service that you program will need to store and retrieve data, and those are the two fundamental purposes of storage.

But it's not just about storing data – it's also about fetching it. We use a database to achieve this. A database is a software layer that helps us store and retrieve data.

These two primary types of operations, storing and retrieving, are also variously called 'set, get', 'store, fetch', 'write, read' and so on. To interact with storage, you will need to go through the database, which acts as an intermediary for you to conduct these fundamental operations.

The word "storage" can sometimes fool us into thinking about it in physical terms. If I "store" my bike in the shed, I can expect it to be there when I next open the shed.

But that doesn't always happen in the computing world. Storage can broadly be of two types: "Memory" storage and "Disk" storage.

Of these two, the disk storage tends to be the more robust and "permanent" (not truly permanent, so we often use the word "persistent" storage instead). Disk storage is persistent storage. This means that when you save something to Disk, and turn the power off, or restart your server, that data will "persist". It won't be lost.

However, if you leave data in "Memory" then that usually gets wiped away when you shut down or restart, or otherwise lose power.

The computer you use everyday has both these storage types. Your hard disk is

"persistent" Disk storage, and your RAM is transient Memory storage.

On servers, if the data you're keeping track of is only useful during a session of that server, then it makes sense to keep it in Memory. This is much faster and less expensive than writing things to a persistent database.

For example, a single session may mean when a user is logged in and using your site. After they log out, you may not need to hold on to bits of data that you collected during the session.

But whatever you do want to hold on to (like shopping cart history) you will put in persistent Disk storage. That way you can access that data the next time the user logs in, and they will have a seamless experience.

Ok, so this seems quite simple and basic, and it's meant to be. This is a primer. Storage can get very complex. If you take a look at the range of storage products and solutions your head will spin.

This is because different use-cases require different types of storage. They key to choosing the right storage types for your system depends on a lot of factors and the needs of your application, and how users interact with it. Other factors include:

These questions and the conclusions require you to consider your trade-offs carefully. Is consistency more important than speed? Do you need the database to service millions of operations per minute or only for nightly updates? I will be dealing with these concepts in sections later, so don't worry if you've no idea what they are.

"Latency" and "Throughput" are terms you're going to hear a lot of as you start to get more experienced with designing systems to support the front end of your application. They are very fundamental to the experience and performance of your application and the system as a whole. There is often a tendency to use these terms in a broader sense than intended, or out of context, but let's fix that.

Latency is simply the measure of a duration. What duration? The duration for an action to complete something or produce a result. For example: for data to move from one place in the system to another. You may think of it as a lag, or just simply the time taken to complete an operation.

The most commonly understood latency is the "round trip" network request - how long does it take for your front end website (client) to send a query to your server, and get a response back from the server.

When you're loading a site, you want this to be as fast and as smooth as possible. In other words you want low latency. Fast lookups means low latency. So finding a value in an array of elements is slower (higher latency, because you need to iterate over each element in the array to find the one you want) than finding a value in a hash-table (lower latency, because you simply look up the data in "constant" time , by using the key. No iteration needed.).

Similarly, reading from memory is much faster than reading from a disk (read more here). But both have latency, and your needs will determine which type of storage you pick for which data.

In that sense, latency is the inverse of speed. You want higher speeds, and you want lower latency. Speed (especially on network calls like via HTTP) is determined also by the distance. So, latency from London to another city, will be impacted by the distance from London.

As you can imagine, you want to design a system to avoid pinging distant servers, but then storing things in memory may not be feasible for your system. These are the tradeoffs that make system design complex, challenging and extremely interesting!

For example, websites that show news articles may prefer uptime and availability over loading speed, whereas online multiplayer games may require availability and super low latency. These requirements will determine the design and investment in infrastructure to support the system's special requirements.

This can be understood as the maximum capacity of a machine or system. It's often used in factories to calculate how much work an assembly line can do in an hour or a day, or some other unit of time measurement.

For example an assembly line can assemble 20 cars per hour, which is its throughput. In computing it would be the amount of data that can be passed around in a unit of time. So a 512 Mbps internet connection is a measure of throughput - 512 Mb (megabits) per second.

Now imagine freeCodeCamp's web-server. If it receives 1 million requests per second, and can serve only 800,000 requests, then its throughput is 800,000 per second. You may end up measuring the throughput in terms of bits instead of requests, so it would be N bits per second.

In this example, there is a bottleneck because the server cannot handle more than N bits a second, but the requests are more than that. A bottleneck is therefore the constraint on a system. A system is only as fast as its slowest bottleneck.

If one server can handle 100 bits per second, and another can handle 120 bits per second and a third can handle only 50, then the overall system will be operating at 50bps because that is the constraint - it holds up the speed of the other servers in a given system.

So increasing throughput anywhere other than the bottleneck may be a waste - you may want to just increase throughput at the lowest bottleneck first.

You can increase throughput by buying more hardware (horizontal scaling) or increasing the capacity and performance of your existing hardware (vertical scaling) or a few other ways.

Increasing throughput may sometimes be a short term solution, and so a good systems designer will think through the best ways to scale the throughput of a given system including by splitting up requests (or any other form of "load"), and distributing them across other resources etc. The key point to remember is what throughput is, what a constraint or bottleneck is, and how it impacts a system.

Fixing latency and throughput are not isolated, universal solutions by themselves, nor are they correlated to each other. They have impacts and considerations across the system, so it's important to understand the system as a whole, and the nature of the demands that will be placed on the system over time.

Software engineers aim to build systems that are reliable. A reliable system is one that consistently satisfies a user's needs, whenever that user seeks to have that need satisfied. A key component of that reliability is Availability.

It's helpful to think of availability as the resiliency of a system. If a system is robust enough to handle failures in the network, database, servers etc, then it can generally be considered to be a fault-tolerant system - which makes it an available system.

Of course, a system is a sum of its parts in many senses, and each part needs to be highly available if availability is relevant to the end user experience of the site or app.

To quantify the availability of a system, we calculate the percentage of time that the system's primary functionality and operations are available (the uptime) in a given window of time.

The most business-critical systems would need to have a near-perfect availability. Systems that support highly variable demands and loads with sharp peaks and troughs may be able to get away with slightly lower availability during off-peak times.

It all depends on the use and nature of the system. But in general, even things that have low, but consistent demands or an implied guarantee that the system is "on-demand" would need to have high availability.

Think of a site where you backup your pictures. You don't always need to access and retrieve data from this - it's mainly for you to store things in. You would still expect it to always be available any time you login to download even just a single picture.

A different kind of availability can be understood in the context of the massive e-commerce shopping days like Black Friday or Cyber Monday sales. On these particular days demand will skyrocket and millions will try to access the deals simultaneously. That would require an extremely reliable and high-availability system design to support those loads.

A commercial reason for high availability is simply that any downtime on the site will result in the site losing money. Also, it could be really bad for reputation, for example, where the service is a service used by other businesses to offer services. If AWS S3 goes down, a lot of companies will suffer, including Netflix, and that is not good.

So uptimes are extremely important for success. It is worth remembering that commercial availability numbers are calculated based on annual availability, so a downtime of 0.1% (i.e. availability of 99.9%) is 8.77 hours a year!

Hence, uptimes are extremely high sounding. It is common to see things like 99.99% uptime (52.6 minutes of downtime per year). Which is why it is now common to refer to uptimes in terms of "nines" - the number of nines in the uptime assurance.

In today's world that is unacceptable for large-scale or mission critical services. Which is why these days "five nines" is considered the ideal availability standard because that translates to a little over 5 minutes of downtime per year.

In order to make online services competitive and meet the market's expectations, online service providers typically offer Service Level Agreements/Assurances. These are a set of guaranteed service level metrics. 99.999% uptime is one such metric and is often offered as part of premium subscriptions.

In the case of database and cloud service providers this can be offered even on the trial or free tiers if a customer's core use for that product justifies the expectation of such a metric.

In many cases failing to meet the SLA will give the customer a right to credits or some other form of compensation for the provider's failure to meet that assurance. Here, by way of example, is Google's SLA for the Maps API.

SLAs are therefore a critical part of the overall commercial and technical consideration when designing a system. It is especially important to consider whether availability is in fact a key requirement for a part of a system, and which parts require high availability.

When designing a high availability (HA) system, then, you need to reduce or eliminate "single points of failure". A single point of failure is an element in the system that is the sole element that can produce that undesirable loss of availability.

You eliminate single points of failure by designing 'redundancy' into the system. Redundancy is basically making 1 or more alternatives (i.e. backups) to the element that is critical for high availability.

So if your app needs users to be authenticated to use it, and there is only one authentication service and back end, and that fails, then, because that is the single point of failure, your system is no longer usable. By having two or more services that can handle authentication, you have added redundancy and eliminated (or reduced) single points of failure.

Therefore, you need to understand and de-compose your system into all its parts. Map out which ones are likely to cause single points of failure, which ones are not tolerant of such failure, and which parts can tolerate them. Because engineering HA requires tradeoffs and some of these tradeoffs may be expensive in terms of time, money and resources.

Caching! This is a very fundamental and easy-to-understand technique to speed up performance in a system. Thus caching helps to reduce "latency" in a system.

In our daily lives, we use caching as a matter of common-sense (most of the time. ). If we live next door to a supermarket, we still want to buy and store some basics in our fridge and our food cupboard. This is caching. We could always step out, go next door, and buy these things every time we want food – but if its in the pantry or fridge, we reduce the time it takes to make our food. That's caching.

Similarly, in software terms, if we end up relying on certain pieces of data often, we may want to cache that data so that our app performs faster.

This is often true when it's faster to retrieve data from Memory rather than disk because of the latency in making network requests. In fact many websites are cached (especially if content doesn't change frequently) in CDNs so that it can be served to the end user much faster, and it reduces load on the backend servers.

Another context in which caching helps could be where your backend has to do some computationally intensive and time consuming work. Caching previous results that converts your lookup time from a linear O(N) time to constant O(1) time could be very advantageous.

Likewise, if your server has to make multiple network requests and API calls in order to compose the data that gets sent back to the requester, then caching data could reduce the number of network calls, and thus the latency.

If your system has a client (front end), and a server and databases (backend) then caching can be inserted on the client (e.g. browser storage), between the client and the server (e.g. CDNs), or on the server itself. This would reduce over-the-network calls to the database.

So caching can occur at multiple points or levels in the system, including at the hardware (CPU) level.

You may have noticed that the above examples are implicitly handy for "read" operations. Write operations are not that different, in main principles, with the following added considerations:

So let's end with some high-level, and non-binding conclusions. Generally, caching works best when used to store static or infrequently changing data, and when the sources of change are likely to be single operations rather than user-generated operations.

Where consistency and freshness in data is critical, caching may not be an optimal solution, unless there is another element in the system that efficiently refreshes the caches at intervals that do not adversely impact the purpose and user experience of the application.

Proxy. What? Many of us have heard of proxy servers. We may have seen configuration options on some of our PC or Mac software that talk about adding and configuring proxy servers, or accessing "via a proxy".

So let's understand that relatively simple, widely used and important piece of tech. This is a word that exists in the English language completely independent of computer science, so let's start with that definition.

Source: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/proxy

Now you can eject most of that out of your mind, and hold on to one key word: "substitute".

In computing, a proxy is typically a server, and it is a server that acts as a middleman between a client and another server. It literally is a bit of code that sits between client and server. That's the crux of proxies.

In case you need a refresher, or aren't sure of the definitions of client and server, a "client" is a process (code) or machine that requests data from another process or machine (the "server"). The browser is a client when it requests data from a backend server.

The server serves the client, but can also be a client - when it retrieves data from a database. Then the database is the server, the server is the client (of the database) and also a server for the front-end client (browser).

Source: https://teoriadeisegnali.it/appint/html/altro/bgnet/clientserver.html#figure2

As you can see from the above, the client-server relationship is bi-directional. So one thing can be both the client and server. If there was a middleman server that received requests, then sent them to another service, then forwards the response it got from that other service back to the originator client, that would be a proxy server.

Going forward we will refer to clients as clients, servers as servers and proxies as the thing between them.

So when a client sends a request to a server via the proxy, the proxy may sometimes mask the identity of the client - to the server, the IP address that comes through in the request may be the proxy and not the originating client.

For those of you who access sites or download things that otherwise are restricted (from the torrent network for example, or sites banned in your country), you may recognize this pattern - it's the principle on which VPNs are built.

Before we move a bit deeper, I want to call something out - when generally used, the term proxy refers to a "forward" proxy. A forward proxy is one where the proxy acts on behalf of (substitute for) the client in the interaction between client and server.

This is distinguished from a reverse proxy - where the proxy acts on behalf of a server. On a diagram it would look the same - the proxy sits between the client and the server, and the data flows are the same client proxy server.

The key difference is that a reverse proxy is designed substitute for the server. Often clients won't even know that the network request got routed through a proxy and the proxy passed it on to the intended server (and did the same thing with the server's response).

So, in a forward proxy, the server won't know that the client's request and its response are traveling through a proxy, and in a reverse proxy the client won't know that the request and response are routed through a proxy.

Proxies feel kinda sneaky :)

But in systems design, especially for complex systems, proxies are useful and reverse proxies are particularly useful. Your reverse proxy can be delegated a lot of tasks that you don't want your main server handling - it can be a gatekeeper, a screener, a load-balancer and an all around assistant.

So proxies can be useful but you may not be sure why. Again, if you've read my other stuff you'd know that I firmly believe that you can understand things properly only when you know why they exist - knowing what they do is not enough.

If you think about the two words, load and balance, you will start to get an intuition as to what this does in the world of computing. When a server simultaneously receives a lot of requests, it can slow down (throughput reduces, latency rises). After a point it may even fail (no availability).

You can give the server more muscle power (vertical scaling) or you can add more servers (horizontal scaling). But now you got to work out how the income requests get distributed to the various servers - which requests get routed to which servers and how to ensure they don't get overloaded too? In other words, how do you balance and allocate the request load?

Enter load balancers. Since this article is an introduction to principles and concepts, they are, of necessity, very simplified explanations. A load balancer's job is to sit between the client and server (but there are other places it can be inserted) and work out how to distribute incoming request loads across multiple servers, so that the end user (client's) experience is consistently fast, smooth and reliable.

So load balancers are like traffic managers who direct traffic. And they do this to maintain availability and throughput.

When understanding where a load balancer is inserted in the system's architecture, you can see that load balancers can be thought of as reverse proxies. But a load balancer can be inserted in other places too - between other exchanges - for example, between your server and your database.

So how does the load balancer decide how to route and allocate request traffic? To start with, every time you add a server, you need to let your load balancer know that there is one more candidate for it to route traffic to.

If you remove a server, the load balancer needs to know that too. The configuration ensures that the load balancer knows how many servers it has in its go-to list and which ones are available. It is even possible for the load balancer to be kept informed on each server's load levels, status, availability, current task and so on.

Once the load balancer is configured to know what servers it can redirect to, we need to work out the best routing strategy to ensure there is proper distribution amongst the available servers.

A naive approach to this is for the load balancer to just randomly pick a server and direct each incoming request that way. But as you can imagine, randomness can cause problems and "unbalanced" allocations where some servers get more loaded than others, and that could affect performance of the overall system negatively.

Another method that can be intuitively understood is called "round robin". This is the way many humans process lists that loop. You start at the first item in the list, move down in sequence, and when you're done with the last item you loop back up to the top and start working down the list again.

The load balancer can do this too, by just looping through available servers in a fixed sequence. This way the load is pretty evenly distributed across your servers in a simple-to-understand and predictable pattern.

You can get a little more "fancy" with the round robin by "weighting" some services over others. In the normal, standard round robin, each server is given equal weight (let's say all are given a weighting of 1). But when you differently weight servers, then you can have some servers with a lower weighting (say 0.5, if they're less powerful), and others can be higher like 0.7 or 0.9 or even 1.

Then the total traffic will be split up in proportion to those weights and allocated accordingly to the servers that have power proportionate to the volume of requests.

More sophisticated load balancers can work out the current capacity, performance, and loads of the servers in their go-to list and allocate dynamically according to current loads and calculations as to which will have the highest throughput, lowest latency etc. It would do this by monitoring the performance of each server and deciding which ones can and cannot handle the new requests.

You can configure your load balancer to hash the IP address of incoming requests, and use the hash value to determine which server to direct the request too. If I had 5 servers available, then the hash function would be designed to return one of five hash values, so one of the servers definitely gets nominated to process the request.

IP hash based routing can be very useful where you want requests from a certain country or region to get data from a server that is best suited to address the needs from within that region, or where your servers cache requests so that they can be processed fast.

In the latter scenario, you want to ensure that the request goes to a server that has previously cached the same request, as this will improve speed and performance in processing and responding to that request.

If your servers each maintain independent caches and your load balancer does not consistently send identical requests to the same server, you will end up with servers re-doing work that has already been done in as previous request to another server, and you lose the optimization that goes with caching data.

You can also get the load balancer to route requests based on their "path" or function or service that is being provided. For example if you're buying flowers from an online florist, requests to load the "Bouquets on Special" may be sent to one server and credit card payments may be sent to another server.

If only one in twenty visitors actually bought flowers, then you could have a smaller server processing the payments and a bigger one handling all the browsing traffic.

And as with all things, you can get to higher and more detailed levels of complexity. You can have multiple load balancers that each have different server selection strategies! And if yours is a very large and highly trafficked system, then you may need load balancers for load balancers.

Ultimately, you add pieces to the system until your performance is tuned to your needs (your needs may look flat, or slow upwards mildly over time, or be prone to spikes!).

We've talked about VPNs (for forward proxies) and load-balancing (for reverse proxies), but there are more examples here.

One of the slightly more tricky concepts to understand is hashing in the context of load balancing. So it gets its own section.

In order to understand this, please first understand how hashing works at a conceptual level. The TL;DR is that hashing converts an input into a fixed-size value, often an integer value (the hash).

One of the key principles for a good hashing algorithm or function is that the function must be deterministic, which is a fancy way for saying that identical inputs will generate identical outputs when passed into the function. So, deterministic means - if I pass in the string "Code" (case sensitive) and the function generates a hash of 11002, then every time I pass in "Code" it must generate "11002" as an integer. And if I pass in "code" it will generate a different number (consistently).

Sometimes the hashing function can generate the same hash for more than one input - this is not the end of the world and there are ways to deal with it. In fact it becomes more likely the more the range of unique inputs are. But when more than one input deterministically generates the same output, it's called a "collision".

With this in firmly in mind, let's apply it to routing and directed requests to servers. Let's say you have 5 servers to allocate loads across. An easy to understand method would be to hash incoming requests (maybe by IP address, or some client detail), and then generate hashes for each request. Then you apply the modulo operator to that hash, where the right operand is the number of servers.

For example, this is what your load balancers' pseudo code could look like:

request#1 => hashes to 34 request#2 => hashes to 23 request#3 => hashes to 30 request#4 => hashes to 14 // You have 5 servers => [Server A, Server B ,Server C ,Server D ,Server E] // so modulo 5 for each request. request#1 => hashes to 34 => 34 % 5 = 4 => send this request to servers[4] => Server E request#2 => hashes to 23 => 23 % 5 = 3 => send this request to servers[3] => Server D request#3 => hashes to 30 => 30 % 5 = 0 => send this request to servers[0] => Server A request#4 => hashes to 14 => 14 % 5 = 4 => send this request to servers[4] => Server E

As you can see, the hashing function generates a spread of possible values, and when the modulo operator is applied it brings out a smaller range of numbers that map to the server number.

You will definitely get different requests that map to the same server, and that's fine, as long as there is "uniformity" in the overall allocation to all the servers.

So - what happens if one of the servers that we are sending traffic to dies? The hashing function (refer to the pseudo code snippet above) still thinks there are 5 servers, and the mod operator generates a range from 0-4. But we only have 4 servers now that one has failed, and we are still sending it traffic. Oops.

Inversely, we could add a sixth server but that would never get any traffic because our mod operator is 5, and it will never yield a number that would include the newly added 6th server. Double oops.

// Let's add a 6th server servers => [Server A, Server B ,Server C ,Server D ,Server E, Server F] // let's change the modulo operand to 6 request#1 => hashes to 34 => 34 % 6 = 4 => send this request to servers[4] => Server E request#2 => hashes to 23 => 23 % 6 = 5 => send this request to servers[5] => Server F request#3 => hashes to 30 => 30 % 6 = 0 => send this request to servers[0] => Server A request#4 => hashes to 14 => 14 % 6 = 2 => send this request to servers[2] => Server C We note that the server number after applying the mod changes (though, in this example, not for request#1 and request#3 - but that is just because in this specific case the numbers worked out that way).

In effect, the result is that half the requests (could be more in other examples!) are now being routed to new servers altogether, and we lose the benefits of previously cached data on the servers.

For example, request#4 used to go to Server E, but now goes to Server C. All the cached data relating to request#4 sitting on Server E is of no use since the request is now going to Server C. You can calculate a similar problem for where one of your servers dies, but the mod function keeps sending it requests.

It sounds minor in this tiny system. But on a very large scale system this is a poor outcome. #SystemDesignFail.

So clearly, a simple hashing-to-allocate system does not scale or handle failures well.

Unfortunately this is the part where I feel word descriptions will not be enough. Consistent hashing is best understood visually. But the purpose of this post so far is to give you an intuition around the problem, what it is, why it arises, and what the shortcomings in a basic solution might be. Keep that firmly in mind.

The key problem with naive hashing, as we discussed, is that when (A) a server fails, traffic still gets routed to it, and (B) you add a new server, the allocations can get substantially changed, thus losing the benefits of previous caches.

There are two very important things to keep in mind when digging into consistent hashing:

Please keep these in mind as you watch the below recommended video that explains consistent hashing, as otherwise its benefits may not be obvious.

I strongly recommend this video as it embeds these principles without burdening you with too much detail.

If you're having a little trouble really understanding why this strategy is important in load balancing, I suggest you take a break, then return to the load balancing section and then re-read this again. It's not uncommon for all this to feel very abstract unless you've directly encountered the problem in your work!

We briefly considered that there are different types of storage solutions (databases) designed to suit a number of different use-cases, and some are more specialized for certain tasks than others. At a very high level though, databases can be categorized into two types: Relational and Non-Relational.

A relational database is one that has strictly enforced relationships between things stored in the database. These relationships are typically made possible by requiring the database to represented each such thing (called the "entity") as a structured table - with zero or more rows ("records", "entries") and and one or more columns ("attributes, "fields").

By forcing such a structure on an entity, we can ensure that each item/entry/record has the right data to go with it. It makes for better consistency and the ability to make tight relationships between the entities.

You can see this structure in the table recording "Baby" (entity) data below. Each record ("entry) in the table has 4 fields, which represent data relating to that baby. This is a classic relational database structure (and a formalized entity structure is called a schema).

source: https://web.stanford.edu/class/cs101/table-1-data.html

So the key feature to understand about relational databases is that they are highly structured, and impose structure on all the entities. This structure in enforced by ensuring that data added to the table conforms to that structure. Adding a height field to the table when its schema doesn't allow for it will not be permitted.

Most relational databases support a database querying language called SQL - Structured Query Language. This is a language specifically designed to interact with the contents of a structured (relational) database. The two concepts are quite tightly coupled, so much so that people often referred to a relational database as a "SQL database" (and sometimes pronounced as "sequel" database).

In general, it is considered that SQL (relational) databases support more complex queries (combining different fields and filters and conditions) than non-relational databases. The database itself handles these queries and sends back matching results.

Many people who are SQL database fans argue that without that function, you would have to fetch all the data and then have the server or the client load that data "in memory" and apply the filtering conditions - which is OK for small sets of data but for a large, complex dataset, with millions of records and rows, that would badly affect performance. However, this is not always the case, as we will see when we learn about NoSQL databases.

A common and much-loved example of a relational database is the PostgreSQL (often called "Postgres") database.

ACID transactions are a set of features that describe the transactions that a good relational database will support. ACID = "Atomic, Consistent, Isolation, Durable". A transaction is an interaction with a database, typically read or write operations.

Atomicity requires that when a single transaction comprises of more than one operation, then the database must guarantee that if one operation fails the entire transaction (all operations) also fail. It's "all or nothing". That way if the transaction succeeds, then on completion you know that all the sub-operations completed successfully, and if an operation fails, then you know that all the operations that went with it failed.

For example if a single transaction involved reading from two tables and writing to three, then if any one of those individual operations fails the entire transaction fails. This means that none of those individual operations should complete. You would not want even 1 out of the 3 write transactions to work - that would "dirty" the data in your databases!

Consistency requires that each transaction in a database is valid according to the database's defined rules, and when the database changes state (some information has changed), such change is valid and does not corrupt the data. Each transaction moves the database from one valid state to another valid state. Consistency can be thought of as the following: every "read" operation receives the most recent "write" operation results.

Isolation means that you can "concurrently" (at the same time) run multiple transactions on a database, but the database will end up with a state that looks as though each operation had been run serially ( in a sequence, like a queue of operations). I personally think "Isolation" is not a very descriptive term for the concept, but I guess ACCD is less easy to say than ACID.

Durability is the promise that once the data is stored in the database, it will remain so. It will be "persistent" - stored on disk and not in "memory".

In contrast, a non-relational database has a less rigid, or, put another way, a more flexible structure to its data. The data typically is presented as "key-value" pairs. A simple way of representing this would be as an array (list) of "key-value" pair objects, for example:

// baby names [ < name: "Jacob", rank: ##, gender: "M", year: #### >, < name: "Isabella", rank: ##, gender: "F", year: #### >, < //. >, // . ] Non relational databases are also referred to as "NoSQL" databases, and offer benefits when you do not want or need to have consistently structured data.

Similar to the ACID properties, NoSQL database properties are sometimes referred to as BASE:

Basically Available which states that the system guarantees availability

Soft State means the state of the system may change over time, even without input

Eventual Consistency states that the system will become consistent over a (very short) period of time unless other inputs are received.

Since, at their core, these databases hold data in a hash-table-like structure, they are extremely fast, simple and easy to use, and are perfect for use cases like caching, environment variables, configuration files and session state etc. This flexibility makes them perfect for using in memory (e.g. Memcached) and also in persistent storage (e.g. DynamoDb).

There are other "JSON-like" databases called document databases like the well-loved MongoDb, and at the core these are also "key-value" stores.

This is a complicated topic so I will simply skim the surface for the purpose of giving you a high level overview of what you need for systems design interviews.

Imagine a database table with 100 million rows. This table is used mainly to look up one or two values in each record. To retrieve the values for a specific row you would need to iterate over the table. If it's the very last record that would take a long time!

Indexing is a way of short cutting to the record that has matching values more efficiently than going through each row. Indexes are typically a data structure that is added to the database that is designed to facilitate fast searching of the database for those specific attributes (fields).

So if the census bureau has 120 million records with names and ages, and you most often need to retrieve lists of people belonging to an age group, then you would index that database on the age attribute.

Indexing is core to relational databases and is also widely offered on non-relational databases. The benefits of indexing are thus available in theory for both types of databases, and this is hugely beneficial to optimise lookup times.

While these may sound like things out of a bio-terrorism movie, you're more likely to hear them everyday in the context of database scaling.

Replication means to duplicate (make copies of, replicate) your database. You may remember that when we discussed availability.

We had considered the benefits of having redundancy in a system to maintain high availability. Replication ensures redundancy in the database if one goes down. But it also raises the question of how to synchronize data across the replicas, since they're meant to have the same data. Replication on write and update operations to a database can happen synchronously (at the same time as the changes to the main database) or asynchronously .

The acceptable time interval between synchronising the main and a replica database really depends on your needs - if you really need state between the two databases to be consistent then the replication needs to be rapid. You also want to ensure that if the write operation to the replica fails, the write operation to the main database also fails (atomicity).

But what do you do when you've got so much data that simply replicating it may solve availability issues but does not solve throughput and latency issues (speed)?

At this point you may want to consider "chunking down" your data, into "shards". Some people also call this partitioning your data (which is different from partitioning your hard drive!).

Sharding data breaks your huge database into smaller databases. You can work out how you want to shard your data depending on its structure. It could be as simple as every 5 million rows are saved in a different shard, or go for other strategies that best fit your data, needs and locations served.

Let's move back to servers again for a slightly more advanced topic. We already understand the principle of Availability, and how redundancy is one way to increase availability. We have also walked through some practical considerations when handling the routing of requests to clusters of redundant servers.

But sometimes, with this kind of setup where multiple servers are doing much the same thing, there can arise situations where you need only one server to take the lead.

For example, you want to ensure that only one server is given the responsibility for updating some third party API because multiple updates from different servers could cause issues or run up costs on the third-party's side.

In this case you need to choose that primary server to delegate this update responsibility to. That process is called leader election.

When multiple servers are in a cluster to provide redundancy, they could, amongst themselves, be configured to have one and only one leader. They would also detect when that leader server has failed, and appoint another one to take its place.

The principle is very simple, but the devil is in the details. The really tricky part is ensuring that the servers are "in sync" in terms of their data, state and operations.

There is always the risk that certain outages could result in one or two servers being disconnected from the others, for example. In that case, engineers end up using some of the underlying ideas that are used in blockchain to derive consensus values for the cluster of servers.

In other words, a consensus algorithm is used to give all the servers an "agreed on" value that they can all rely on in their logic when identifying which server is the leader.

Leader Election is commonly implemented with software like etcd, which is a store of key-value pairs that offers both high availability and strong consistency (which is valuable and an unusual combination) by using Leader Election itself and using a consensus algorithm.

So engineers can rely on etcd's own leader election architecture to produce leader election in their systems. This is done by storing in a service like etcd, a key-value pair that represents the current leader.

Since etcd is highly available and strongly consistent, that key-value pair can always be relied on by your system to contain the final "source of truth" server in your cluster is the current elected leader.

In the modern age of continuous updates, push notifications, streaming content and real-time data, it is important to grasp the basic principles that underpin these technologies. To have data in your application updated regularly or instantly requires the use of one of the two following approaches.

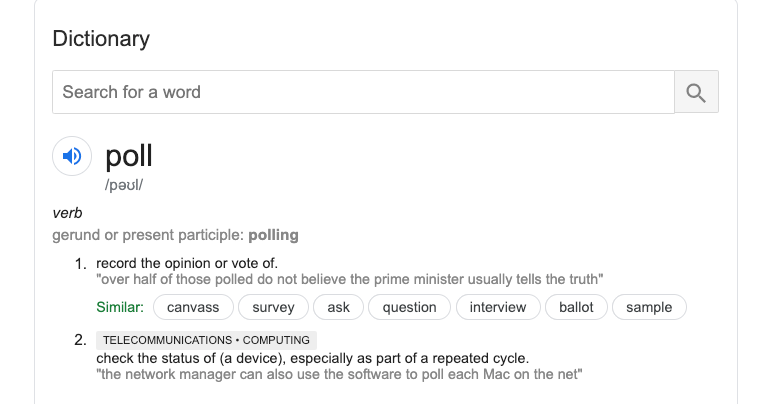

This one is simple. If you look at the wikipedia entry you may find it a bit intense. So instead take a look at its dictionary meaning, especially in the context of computer science. Keep that simple fundamental in mind.

Polling is simply having your client check on a server by sending it a network request and asking for updated data. These requests are typically made at regular intervals like 5 seconds, 15 seconds, 1 minute or any other interval required by your use case.

Polling every few seconds is still not quite the same as real-time, and also comes with the following downsides, especially if you have a million plus simultaneous users:

So polling rapidly is not really efficient or performant, and polling is best used in circumstances when small gaps in data updates is not a problem for your application.

For example, if you built an Uber clone, you may have the driver-side app send driver location data every 5 seconds, and your rider-side app poll for the driver's location every 5 seconds.

Streaming solves the constant polling problem. If constantly hitting the server is necessary, then it's better to use something called web-sockets.

This is a network communication protocol that is designed to work over TCP. It opens a two-way dedicated channel (socket) between a client and server, kind of like an open hotline between two endpoints.

Unlike the usual TCP/IP communication, these sockets are "long-lived" so that its a single request to the server that opens up this hotline for the two-way transfer of data, rather than multiple separate requests. By long-lived, we meant that the socket connection between the machines will last until either side closes it, or the network drops.

You may remember from our discussion on IP, TCP and HTTP that these operate by sending "packets" of data, for each request-response cycle. Web-sockets mean that there is a single request-response interaction (not a cycle really if you think about it!) and that opens up the channel through which two-data is sent in a "stream".

The big difference with polling and all "regular" IP based communication is that whereas polling has the client making requests to the server for data at regular intervals ("pulling" data), in streaming, the client is "on standby" waiting for the server to "push" some data its way. The server will send out data when it changes, and the client is always listening for that. Hence, if the data change is constant, then it becomes a "stream", which may be better for what the user needs.

For example, while using collaborative coding IDEs, when either user types something, it can show up on the other, and this is done via web-sockets because you want to have real-time collaboration. It would suck if what I typed showed up on your screen after you tried to type the same thing or after 3 minutes of you waiting wondering what I was doing!

Or think of online, multiplayer games - that is a perfect use case for streaming game data between players!

To conclude, the use case determines the choice between polling and streaming. In general, you want to stream if your data is "real-time", and if it's OK to have a lag (as little as 15 seconds is still a lag) then polling may be a good option. But it all depends on how many simultaneous users you have and whether they expect the data to be instantaneous. A commonly used example of a streaming service is Apache Kafka.

When you build large scale systems it becomes important to protect your system from too many operations, where such operations are not actually needed to use the system. Now that sounds very abstract. But think of this - how many times have you clicked furiously on a button thinking it's going to make the system more responsive? Imagine if each one of those button clicks pinged a server and the server tried to process them all! If the throughput of the system is low for some reason (say a server was struggling under unusual load) then each of those clicks would have made the system even slower because it has to process them all!

Sometimes it's not even about protecting the system. Sometimes you want to limit the operations because that is part of your service. For example, you may have used free tiers on third-party API services where you're only allowed to make 20 requests per 30 minute interval. if you make 21 or 300 requests in a 30 minute interval, after the first 20, that server will stop processing your requests.

That is called rate-limiting. Using rate-limiting, a server can limit the number of operations attempted by a client in a given window of time. A rate-limit can be calculated on users, requests, times, payloads, or other things. Typically, once the limit is exceeded in a time window, for the rest of that window the server will return an error.

Ok, now you might think that endpoint "protection" is an exaggeration. You're just restricting the users ability to get something out of the endpoint. True, but it is also protection when the user (client) is malicious - like say a bot that is smashing your endpoint. Why would that happen? Because flooding a server with more requests than it can handle is a strategy used by malicious folks to bring down that server, which effectively brings down that service. That's exactly what a Denial of Service (D0S) attack is.

While DoS attacks can be defended against in this way, rate-limiting by itself won't protect you from a sophisticated version of a DoS attack - a distributed DoS. Here distribution simply means that the attack is coming from multiple clients that seem unrelated and there is no real way to identify them as being controlled by the single malicious agent. Other methods need to be used to protect against such coordinated, distributed attacks.

But rate-limiting is useful and popular anyway, for less scary use-cases, like the API restriction one I mentioned. Given how rate-limiting works, since the server has to first check the limit conditions and enforce them if necessary, you need to think about what kind of data structure and database you'd want to use to make those checks super fast, so that you don't slow down processing the request if it's within allowed limits. Also, if you have it in-memory within the server itself, then you need to be able to guarantee that all requests from a given client will come to that server so that it can enforce the limits properly. To handle situations like this it's popular to use a separate Redis service that sits outside the server, but holds the user's details in-memory, and can quickly determine whether a user is within their permitted limits.

Rate limiting can be made as complicated as the rules you want to enforce, but the above section should cover the fundamentals and most common use-cases.

When you design and build large-scale and distributed systems, for that system to work cohesively and smoothly, it is important to exchange information between the components and services that make up the system. But as we have seen before, systems that rely on networks suffer from the same weakness as networks - they are fragile. Networks fail and its not an infrequent occurrence. When networks fail, components in the system are not able to communicate and may degrade the system (best case) or cause the system to fail altogether (worst case). So distributed systems need robust mechanisms to ensure that the communication continues or recovers where it left off, even if there is an "arbitrary partition" (i.e. failure) between components in the system.

Imagine, as an example, that you're booking airline tickets. You get a good price, choose your seats, confirm the booking and you've even paid using your credit card. Now you're waiting for your ticket PDF to arrive in your inbox. You wait, and wait, and it never comes. Somewhere, there was a system failure that didn't get handled or recover properly. A booking system will often connect with airline and pricing APIs to handle the actual flight selection, fare summary, date and time of flight etc. All that gets done while you click through the site's booking UI. But it doesn't have to send you the PDF of the tickets until a few minutes later. Instead the UI can simply confirm that your booking is done, and you can expect the tickets in your inbox shortly. That's a reasonable and common user experience for bookings because the moment of paying and the receipt of the tickets does not have to be simultaneous - the two events can be asynchronous. Such a system would need messaging to ensure that the service (server endpoint) that asynchronously generates the PDF gets notified of a confirmed, paid-for booking, and all the details, and then the PDF can be auto-generated and emailed to you. But if that messaging system fails, the email service would never know about your booking and no ticket would get generated.

Publisher / Subscriber Messaging

This is a very popular paradigm (model) for messaging. The key concept is that publishers 'publish' a message and a subscriber subscribes to messages. To give greater granularity, messages can belong to a certain "topic" which is like a category. These topics are like dedicated "channels" or pipes, where each pipe exclusives handles messages belonging to a specific topic. Subscribers choose which topic they want to subscribe to and get notified of messages in that topic. The advantage of this system is that the publisher and the subscriber can be completely de-coupled - i.e. they don't need to know about each other. The publisher announces, and the subscriber listens for announcements for topics that it is on the lookout for.

A server is often the publisher of messages and there are usually several topics (channels) that get published to. The consumer of a specific topic subscribes to those topics. There is no direct communication between the server (publisher) and the subscriber (could be another server). The only interaction is between publisher and topic, and topic and subscriber.

The messages in the topic are just data that needs to be communicated, and can take on whatever forms you need. So that gives you four players in Pub/Sub: Publisher, Subscriber, Topics and Messages.

So why bother with this? Why not just persist all data to a database and consume it directly from there? Well, you need a system to queue up the messages because each message corresponds to a task that needs to be done based on that message's data. So in our ticketing example, if 100 people make a booking in 35 minutes, putting all that in the database doesn't solve the problem of emailing those 100 people. It just stores a 100 transactions. Pub/Sub systems handle the communication, the task sequencing and the messages get persisted in a database. So the system can offer useful features like "at least once" delivery (messages won't be lost), persistent storage, ordering of messages, "try-again", "re-playability" of messages etc. Without this system, just storing the messages in the database will not help you ensure that the message gets delivered (consumed) and acted upon to successfully complete the task.

Sometimes the same message may get consumed more than once by a subscriber - typically because the network dropped out momentarily, and though the subscriber consumed the message, it didn't let the publisher know. So the publisher will simply re-send it to the subscriber. That's why the guarantee is "at least once" and not "once and only once". This is unavoidable in distributed systems because networks are inherently unreliable. This can raise complications, where the message triggers an operation on the subscriber's side, and that operation could change things in the database (change state in the overall application). What if a single operation gets repeated multiple times, and each time the application's state changes?

The solution to this new problem is called idempotency - which is a concept that is important but not intuitive to grasp the first few times you examine it. It is a concept that can appear complex (especially if you read the wikipedia entry), so for the current purpose, here is a user-friendly simplification from StackOverflow:

In computing, an idempotent operation is one that has no additional effect if it is called more than once with the same input parameters.

So when a subscriber processes a message two or three times, the overall state of the application is exactly what it was after the message was processed the first time. If, for example, at the end of booking your flight tickets and after you entered your credit card details, you clicked on "Pay Now" three times because the system was slow . you would not want to pay 3X the ticket price right? You need idempotency to ensure that each click after the first one doesn't make another purchase and charge your credit card more than once. In contrast, you can post an identical comment on your best friend's newsfeed N number of times. They will all show up as separate comments, and apart from being annoying, that's not actually wrong. Another example is offering "claps" on Medium posts - each clap is meant to increment the number of claps, not be one and only one clap. These latter two examples do not require idempotency, but the payment example does.

There are many flavours of messaging systems, and the choice of system is driven by the use-case to be solved for. Often, people will refer to "event based" architecture which means that the system relies on messages about "events" (like paying for tickets) to process operations (like emailing the ticket). The really commonly talked about services are Apache Kafka, RabbitMQ, Google Cloud Pub/Sub, AWS SNS/SQS.

Over time your system will collect a lot of data. Most of this data is extremely useful. It can give you a view of the health of your system, its performance and problems. It can also give you valuable insight into who uses your system, how they use it, how often, which parts get used more or less, and so on.

This data is valuable for analytics, performance optimization and product improvement. It is also extremely valuable for debugging, not just when you log to your console during development, but in actually hunting down bugs in your test and production environments. So logs help in traceability and audits too.

The key trick to remember when logging is to view it as a sequence of consecutive events, which means the data becomes time-series data, and the tools and databases you use should be specifically designed to help work with that kind of data.

This is the next steps after logging. It answers the question of "What do I do with all that logging data?". You monitor and analyze it. You build or use tools and services that parse through that data and present you with dashboards or charts or other ways of making sense of that data in a human-readable way.

By storing the data in a specialized database designed to handle this kind of data (time-series data) you can plug in other tools that are built with that data structure and intention in mind.

When you are actively monitoring you should also put a system in place to alert you of significant events. Just like having an alert for stock prices going over a certain ceiling or below a certain threshold, certain metrics that you're watching may warrant an alert being sent if they go too high or too low. Response times (latency) or errors and failures are good ones to set up alerting for if they go above an "acceptable" level.

The key to good logging and monitoring is to ensure your data is fairly consistent over time, as working with inconsistent data could result in missing fields that then break the analytical tools or reduce the benefits of the logging.

As promised, some useful resources are as follows:

I hope you enjoyed this long-form guide!

If you would like to learn more about my journey from lawyer to software engineer, check out episode 53 of the freeCodeCamp podcast and also Episode 207 of "Lessons from a Quitter". These provide the blueprint for my career change.

If you are interested in teaching yourself to code, changing careers and becoming a professional coder, or becoming your own technical co-founder, please reach out here. You can also check out my free webinar on Career Change to Code if that is what you're dreaming of.